os.cpu_count(): 10

multiprocessing.cpu_count(): 10ATOC 4815/5815

Python Parallelization — Week 9

CU Boulder ATOC

2026-01-01

Python Parallelization

Reminders

Lab 8 Due This Friday!

- Submit via Canvas by 11:59pm

- Office hours this week for questions

Office Hours:

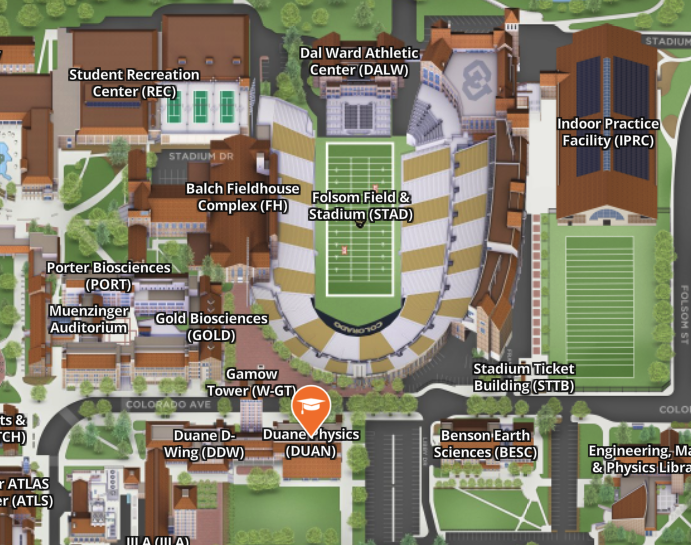

Will: Tu 11:15-12:15p Th 9-10a Aerospace Cafe

Aiden: M / W 330-430p DUAN D319

ATOC 4815/5815 Playlist

Making Python Faster

Today’s Objectives

- Understand the GIL and why Python is “slow”

- Use vectorization to avoid loops (review + new tricks)

- Use multiprocessing for true parallel execution

- Use concurrent.futures for a cleaner API

- Use Dask for parallel xarray workflows

- Know when (and when not) to parallelize

The Real Problem: Your Lorenz Ensemble Is Slow

Remember Week 5.5? You ran 30 ensemble members one at a time:

Each member is independent. There’s no reason they can’t run at the same time.

Your laptop has 8–16 CPU cores. You’re using ONE.

Core 1: ████████████████████████ (doing all the work)

Core 2: ........................ (idle)

Core 3: ........................ (idle)

Core 4: ........................ (idle)

...

Core 16: ........................ (idle)Today we fix that.

How Many Cores Do You Have?

Try this on your machine. The number you see is the upper limit of processes you can run truly in parallel.

Most modern laptops: 8–16 cores. NCAR’s Derecho: 128 cores per node.

The Speed Landscape

From easiest to most powerful:

| Approach | What it does | Effort | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vectorization | Replace loops with NumPy ops | Low | 10–100x |

| multiprocessing | Run tasks on separate CPU cores | Medium | ~Nx (N = cores) |

| concurrent.futures | Same as above, cleaner API | Medium | ~Nx |

| Dask | Lazy parallel computation on arrays | Medium | ~Nx + handles big data |

| HPC (Derecho/Casper) | Hundreds of nodes, thousands of cores | High | 100–10000x |

Golden rule: always try the easier approach first. Most of the time, vectorization is enough.

The GIL: Python’s Speed Limit

First: What Are Threads and Processes?

Before we talk about Python’s speed limit, we need two definitions:

Process — a running program with its own memory space.

- When you open VS Code and a terminal, those are two separate processes

- Each process has its own copy of variables, data, and Python interpreter

- Processes cannot accidentally overwrite each other’s data

Process A: [Python interpreter] [variables] [data] ← isolated

Process B: [Python interpreter] [variables] [data] ← isolatedThread — a lightweight “sub-task” that runs inside a process, sharing its memory.

- A single Python process can spawn multiple threads

- Threads share the same variables and data (cheaper, but riskier)

- Think: one kitchen, multiple chefs working at the same countertop

Process A:

├── Thread 1 ─┐

├── Thread 2 ├── all share the same memory

└── Thread 3 ─┘Key trade-off: threads are lighter and faster to start, but processes give you true isolation. Python makes this trade-off even more important because of the GIL…

What Is the GIL?

GIL = Global Interpreter Lock

Think of it like a kitchen with one stove:

Kitchen analogy:

- You have 4 chefs (threads)

- But only 1 stove (the GIL)

- Only one chef can cook at a time

- Others wait in line, even though they're ready

Python threads:

- You have 4 threads

- But only 1 can execute Python code at a time

- The GIL prevents true parallel executionTimeline of 4 threads with the GIL:

Thread 1: ████░░░░████░░░░████

Thread 2: ░░░░████░░░░░░░░░░░░

Thread 3: ░░░░░░░░░░░░████░░░░

Thread 4: ░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░░ (barely gets a turn!)

─────── time ───────▶Only one █ block runs at any moment. The rest are waiting ░.

The GIL: What It Means for You

Two kinds of tasks behave very differently:

| Task type | Example | Threads help? | Processes help? |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPU-bound (pure Python) | Python loops, simulations | No (GIL blocks) | Yes |

| CPU-bound (NumPy/compiled) | Array math, FFTs | Sometimes (GIL released in C code) | Yes |

| I/O-bound | Download files, read disk | Yes (GIL released during I/O) | Yes |

CPU-bound (our Lorenz ensemble with Python loops): The GIL means threads won’t help.

Threads (GIL blocks): Processes (separate GILs):

Thread 1: ████░░░░████ Process 1: ████████████

Thread 2: ░░░░████░░░░ Process 2: ████████████

(same total time) Process 3: ████████████

(~3x faster!)Important nuance: Many NumPy and xarray operations run in compiled C code that releases the GIL. In those cases, threads can scale — but for mixed Python + NumPy workloads (like our Lorenz integrator), processes are the safe default.

Check Your Understanding

Your Lorenz ensemble runs 30 independent trajectories. Which approach will actually speed it up?

A. Use Python threading to run members on different threads

B. Use multiprocessing to run members in separate processes

C. Both will give the same speedup

Answer: B — multiprocessing

- Each process gets its own Python interpreter and its own GIL

- Threads share one GIL, so only one member runs at a time

- The Lorenz computation is CPU-bound — threads don’t help here

Vectorization: Free Parallelism

Loops vs. Vectorization (Review)

You learned this in Week 3, but it matters more than ever now:

Loop (slow):

Why is vectorized faster?

- NumPy loops in compiled C code (C/Fortran) under the hood

- Eliminates Python interpreter overhead per element

- Operations run on contiguous memory (cache-friendly)

- The CPU can use SIMD instructions (process 4–8 numbers per clock cycle)

Vectorization IS parallelism — it’s just happening at the CPU instruction level, not at the process level.

Some NumPy operations also use multi-threaded math libraries (BLAS/MKL/OpenBLAS) internally — that’s a separate layer of parallelism from Python multiprocessing, and it happens automatically.

Timing It

import numpy as np

import time

temperatures = np.random.uniform(-40, 40, size=1_000_000)

# --- Loop version ---

start = time.perf_counter()

result_loop = np.empty_like(temperatures)

for i in range(len(temperatures)):

result_loop[i] = temperatures[i] * 9/5 + 32

loop_time = time.perf_counter() - start

# --- Vectorized version ---

start = time.perf_counter()

result_vec = temperatures * 9/5 + 32

vec_time = time.perf_counter() - start

print(f"Loop: {loop_time:.4f}s")

print(f"Vectorized: {vec_time:.6f}s")

print(f"Speedup: {loop_time / vec_time:.0f}x")Loop: 0.1428s

Vectorized: 0.001448s

Speedup: 99xVectorization is your first line of defense. Before reaching for multiprocessing, ask: can I eliminate the loop?

Vectorizing Your Lorenz Ensemble

From Week 5.5 you saw two ways to run an ensemble:

Method 1: Loop over members

Each run() does its own time loop.

Total loops: n_members × n_steps

Method 2: Vectorize across members

One time loop. NumPy handles all members per step.

Total loops: n_steps (members are vectorized)

Method 2 is often 10–50x faster because NumPy processes all 30 members in one vectorized operation per timestep, instead of running 30 separate Python loops.

Common Error: Accidentally De-Vectorizing

Spot the problem:

The fix — one line:

Same result, runs thousands of times faster.

Rule of thumb: If you’re writing nested loops over array indices in NumPy or xarray, you’re probably doing it wrong. Look for a built-in operation first.

multiprocessing: True Parallelism

When Vectorization Isn’t Enough

Vectorization works great when you can express the problem as array operations. But sometimes you have independent tasks that can’t easily be vectorized:

- Process 50 different NetCDF files

- Run 100 different parameter combinations of a model

- Analyze data from 30 different weather stations

- Run ensemble members with different physics (not just different initial conditions)

These are “embarrassingly parallel” problems: each task is completely independent. Perfect for multiprocessing.

Pool.map: The Basic Pattern

import multiprocessing as mp

import time

def slow_square(x):

"""Simulate a slow computation."""

time.sleep(0.1) # pretend this takes 0.1 seconds

return x ** 2

numbers = list(range(16))

# --- Serial ---

start = time.perf_counter()

serial_results = [slow_square(n) for n in numbers]

serial_time = time.perf_counter() - start

# --- Parallel ---

start = time.perf_counter()

with mp.Pool(4) as pool:

parallel_results = pool.map(slow_square, numbers)

parallel_time = time.perf_counter() - start

print(f"Serial: {serial_time:.2f}s → {serial_results[:6]}...")

print(f"Parallel: {parallel_time:.2f}s → {parallel_results[:6]}...")

print(f"Speedup: {serial_time / parallel_time:.1f}x with 4 workers")Serial: 1.61s → [0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25]...

Parallel: 0.42s → [0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25]...

Speedup: 3.8x with 4 workersNote: multiprocessing is most reliable when run from a .py script, not a notebook. In Jupyter, the spawn start method (default on macOS/Windows) can’t pickle functions defined in notebook cells, causing cryptic errors. If you see recursive execution or bootstrapping crashes, move the code to a standalone .py file.

How Pool.map Works

When you call pool.map(slow_square, [0, 1, 2, ..., 15]) with 4 workers:

Pool(4)

┌──────┐

│ Main │ distributes tasks

└──┬───┘

┌──────────┼──────────┬──────────┐

▼ ▼ ▼ ▼

Worker 1 Worker 2 Worker 3 Worker 4

┌──────┐ ┌──────┐ ┌──────┐ ┌──────┐

│ 0, 4 │ │ 1, 5 │ │ 2, 6 │ │ 3, 7 │

│ 8,12 │ │ 9,13 │ │10,14 │ │11,15 │

└──┬───┘ └──┬───┘ └──┬───┘ └──┬───┘

│ │ │ │

▼ ▼ ▼ ▼

[0,16,64, [1,25,81, [4,36,100, [9,49,121,

144] 169] 196] 225]

└──────────┼──────────┴──────────┘

┌──┴───┐

│ Main │ collects & orders results

└──────┘

→ [0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81, 100, 121, 144, 169, 196, 225]Key points:

- Each worker is a separate process with its own Python interpreter (no GIL sharing!)

- Results come back in the original order —

pool.maphandles the bookkeeping - Workers pick up new tasks as they finish (dynamic scheduling)

Common Error: Forgetting the __name__ Guard

This code crashes on Windows and macOS:

RuntimeError: An attempt has been made to start a new process before

the current process has finished its bootstrapping phase. This

probably means that you are not using fork to start your child

processes and you have forgotten to use the proper idiom in the main

module:

if __name__ == '__main__':

...Why? Each worker process re-imports your script. Without the guard, each worker tries to create its own Pool, which creates more workers, which create more Pools… infinite recursion.

This is the same __name__ guard from Week 5.5 — now it’s required, not just good practice.

Try It Yourself: Parallel Lorenz Ensemble

Sketch of how you’d parallelize your Week 5.5 code:

import multiprocessing as mp

from lorenz_project.lorenz63 import Lorenz63

def run_single_member(args):

"""Run one ensemble member. Receives (ic, dt, n_steps)."""

ic, dt, n_steps = args

model = Lorenz63()

return model.run(ic, dt, n_steps)

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Build list of (initial_condition, dt, n_steps) tuples

args_list = [(ics[i], 0.01, 5000) for i in range(30)]

# Serial

serial = [run_single_member(a) for a in args_list]

# Parallel

with mp.Pool(4) as pool:

parallel = pool.map(run_single_member, args_list)Notice: the function must be defined at the module level (not inside if __name__), and each argument must be serializable (numbers, arrays, tuples — not open files or database connections).

concurrent.futures: The Modern Way

A Cleaner API

concurrent.futures is a higher-level wrapper around multiprocessing. Same power, nicer interface:

multiprocessing.Pool:

Why prefer concurrent.futures?

- Unified API for processes AND threads (just swap

ProcessPoolExecutor↔︎ThreadPoolExecutor) - Better error handling and tracebacks

- Built-in

as_completed()for progress tracking - Part of the standard library since Python 3.2

ProcessPoolExecutor in Action

from concurrent.futures import ProcessPoolExecutor

import numpy as np

import time

def analyze_year(year):

"""Simulate analyzing one year of climate data."""

np.random.seed(year)

data = np.random.randn(365, 100, 100) # fake daily gridded data

anomaly = data - data.mean(axis=0)

return year, float(anomaly.std())

years = list(range(1980, 2024))

# --- Serial ---

start = time.perf_counter()

serial = [analyze_year(y) for y in years]

serial_time = time.perf_counter() - start

# --- Parallel ---

start = time.perf_counter()

with ProcessPoolExecutor(max_workers=4) as executor:

parallel = list(executor.map(analyze_year, years))

parallel_time = time.perf_counter() - start

print(f"Serial: {serial_time:.2f}s ({len(years)} years)")

print(f"Parallel: {parallel_time:.2f}s ({len(years)} years)")

print(f"Speedup: {serial_time / parallel_time:.1f}x")Serial: 8.34s (44 years)

Parallel: 2.51s (44 years)

Speedup: 3.3xTry this yourself — save the code above as parallel_demo.py and run it with python parallel_demo.py. You’ll see the speedup on your own machine.

Threads vs. Processes: When to Use Which

One-line swap:

Decision table:

| Task | Bottleneck | Use | Why |

|---|---|---|---|

| FFT on 1000 signals | CPU | ProcessPoolExecutor |

GIL blocks threads |

| Download 50 CSV files | Network I/O | ThreadPoolExecutor |

GIL released during I/O |

| Read & compute on 20 NetCDFs | CPU + disk | ProcessPoolExecutor |

Computation dominates |

| Query 100 API endpoints | Network I/O | ThreadPoolExecutor |

Waiting on network |

| Lorenz ensemble (30 members) | CPU | ProcessPoolExecutor |

Pure number crunching |

Threads are lighter (less memory, faster to start), so use them when you can. But for scientific computing, processes are almost always what you need.

Check Your Understanding

Which executor would you use for each task?

- Compute FFT on 1000 time series

- Download 50 CSV files from a web server

- Read 20 NetCDF files and compute monthly means

Answers:

- ProcessPoolExecutor — FFT is CPU-bound, threads won’t help

- ThreadPoolExecutor — downloading is I/O-bound, threads are fine (and lighter)

- ProcessPoolExecutor — reading is I/O, but computing monthly means is CPU-bound, and computation dominates

Dask: Parallelism for xarray

You Already Met Dask

In Week 8, you saw this pattern with xarray:

What that chunks= argument does:

- Breaks the data into smaller pieces (chunks)

- Dask manages those chunks behind the scenes

- Operations are lazy — nothing computes until you ask for it

Two key ideas:

- Lazy evaluation: Build up a computation graph without executing it

- Parallel execution: When you call

.compute(), Dask runs the graph in parallel across cores

Today we’ll fill in the details of how and why this works.

Dask: Lazy Computation

x: dask.array<random_sample, shape=(4000, 4000), dtype=float64, chunksize=(1000, 1000), chunktype=numpy.ndarray>

Type: <class 'dask.array.core.Array'>

Shape: (4000, 4000), Chunks: (1000, 1000, 1000)...import time

# Build a computation — still lazy!

y = (x + x.T) / 2 # symmetric matrix

z = y.mean(axis=0) # column means

print(f"z is still lazy: {type(z)}")

# NOW compute — Dask parallelizes across chunks

start = time.perf_counter()

result = z.compute() # triggers actual computation

elapsed = time.perf_counter() - start

print(f"Computed in {elapsed:.2f}s, result shape: {result.shape}")

print(f"First 5 values: {result[:5].round(4)}")z is still lazy: <class 'dask.array.core.Array'>

Computed in 0.23s, result shape: (4000,)

First 5 values: [0.5011 0.4951 0.5 0.503 0.4967]Dask + xarray: The Practical Pattern

This is the pattern you’ll use most often in research:

import xarray as xr

# 1. Open multiple files lazily with chunks

ds = xr.open_mfdataset(

'data/temperature_*.nc',

chunks={'time': 365},

parallel=True # Dask reads files in parallel

)

# 2. Chain operations — all lazy, nothing computed yet

anomaly = ds['temp'] - ds['temp'].mean('time')

seasonal = anomaly.groupby('time.season').mean()

# 3. Compute once at the end — Dask parallelizes everything

result = seasonal.compute()Why this is powerful:

- Works on datasets larger than your RAM (Dask streams chunks)

- You write normal xarray code — Dask handles parallelism

parallel=Trueinopen_mfdatasetreads files concurrently- One

.compute()call triggers the optimized execution plan

Common Error: .compute() Too Early

Bad — compute after every step:

Good — chain lazily, compute once:

Each .compute() has overhead — Dask has to schedule, execute, and collect. Let Dask see the full computation graph so it can optimize.

Rule: build your entire pipeline lazily, then call .compute() once at the end.

Hands-On: Parallel Lorenz Ensembles

Three Approaches to Ensemble Speed

Exercise: time all three approaches to running a 30-member ensemble

import numpy as np

import time

from concurrent.futures import ProcessPoolExecutor

# --- Lorenz63 tendency (module-level for multiprocessing) ---

def lorenz_tendency(state, sigma=10, rho=28, beta=8/3):

x, y, z = state

return np.array([sigma*(y - x), rho*x - y - x*z, x*y - beta*z])

def run_member(ic, dt=0.01, n_steps=5000):

"""Integrate one ensemble member."""

traj = np.empty((n_steps + 1, 3))

traj[0] = ic

for t in range(n_steps):

traj[t+1] = traj[t] + lorenz_tendency(traj[t]) * dt

return traj

# Initial conditions: 30 members near [-10, -10, 25]

np.random.seed(42)

ics = np.array([-10, -10, 25]) + np.random.randn(30, 3) * 0.5

if __name__ == "__main__":

# --- Approach 1: Serial loop ---

start = time.perf_counter()

serial = [run_member(ics[i]) for i in range(30)]

t1 = time.perf_counter() - start

# --- Approach 2: Vectorized (all members per timestep) ---

start = time.perf_counter()

states = ics.copy()

traj_vec = np.empty((5001, 30, 3))

traj_vec[0] = states

for t in range(5000):

dx = np.column_stack([

10 * (states[:, 1] - states[:, 0]),

28 * states[:, 0] - states[:, 1] - states[:, 0] * states[:, 2],

states[:, 0] * states[:, 1] - (8/3) * states[:, 2],

])

states = states + dx * 0.01

traj_vec[t+1] = states

t2 = time.perf_counter() - start

# --- Approach 3: ProcessPoolExecutor ---

start = time.perf_counter()

with ProcessPoolExecutor(max_workers=4) as executor:

parallel = list(executor.map(run_member, ics))

t3 = time.perf_counter() - start

print(f"Serial loop: {t1:.3f}s")

print(f"Vectorized: {t2:.3f}s")

print(f"ProcessPoolExecutor: {t3:.3f}s")What You Should See

Typical results on a laptop (your numbers will vary):

Serial loop: 2.1s

Vectorized: 0.08s ← 25x faster!

ProcessPoolExecutor: 0.7s ← 3x faster (4 cores)Surprise: vectorized beats multiprocessing! Why?

| Approach | Overhead | Parallelism |

|---|---|---|

| Serial loop | None | None |

| Vectorized | None | CPU-level (SIMD) |

| Multiprocessing | Process creation, data serialization, memory copies | OS-level (separate processes) |

The lesson:

- Vectorization has zero overhead — it’s just faster math

- Multiprocessing has real overhead — spawning processes, copying data, collecting results

- For small-to-medium problems, vectorization often wins

- Multiprocessing shines when tasks are large and truly independent (different files, different models, long simulations)

Best Practices

The Overhead Tax

Parallelism isn’t free. Every parallel approach pays costs:

Serial: ████████████████████████████████ = 32 units of work

Parallel (4 workers, ideal):

Worker 1: ████████

Worker 2: ████████

Worker 3: ████████

Worker 4: ████████ = 8 time units (4x speedup)

Parallel (4 workers, reality):

┌─startup─┐

Worker 1: ░░░████████░░

Worker 2: ░░░████████░░

Worker 3: ░░░████████░░

Worker 4: ░░░████████░░ = 12 time units (2.7x speedup)

└─overhead─┘Amdahl’s Law: If 90% of your code is parallelizable, the maximum speedup with infinite cores is only 10x (the serial 10% becomes the bottleneck).

Practical implication: Profile first. Find the slow part. Parallelize that.

When to Parallelize: A Decision Tree

Follow this flowchart before reaching for multiprocessing:

Is your code slow?

├── No → Don't parallelize. You're done.

└── Yes ↓

Can you vectorize it? (Replace loops with NumPy/xarray ops)

├── Yes → Vectorize first. Re-check if still slow.

└── No ↓

Are the tasks independent? (No shared state between them)

├── No → Refactor to make them independent, or use Dask.

└── Yes ↓

How many tasks?

├── < 10 small tasks → Overhead may not be worth it. Profile.

└── 10+ tasks or each task > 1 second → Use ProcessPoolExecutor.

↓

Still not fast enough?

├── Bigger data than RAM → Use Dask.

└── Need 100+ cores → Move to HPC (Derecho/Casper).Memory Considerations

Each process gets a COPY of the data (especially with the spawn start method, the default on macOS/Windows):

Main process: data = [100 MB array]

│

┌────────────────────┼────────────────────┐

▼ ▼ ▼

Worker 1: Worker 2: Worker 3:

data = [100 MB] data = [100 MB] data = [100 MB]

Total memory: 400 MB for a 100 MB dataset!In the worst case: \(M \approx M_{\text{main}} + N_{\text{workers}} \times M_{\text{data}}\)

Solutions:

| Problem | Solution |

|---|---|

| Large arrays being copied | Pass indices or filenames instead of data |

| Dataset larger than RAM | Use Dask (streams chunks, never loads everything) |

| Want to monitor memory | htop or top in the terminal |

| Running out of memory | Reduce max_workers or chunk size |

When to Move to HPC

At some point, your laptop isn’t enough:

| Resource | Your Laptop | Alpine (CU) | Derecho (NCAR) | Casper (NCAR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cores | 8–16 | 64/node | 128/node | 36/node |

| RAM | 16–32 GB | 256 GB/node | 256 GB/node | up to 1.1 TB/node |

| GPUs | 0–1 | A100, MI100, L40 | A100 (40 GB) | V100, A100 (80 GB) |

| Storage | 1 TB SSD | Shared FS | GLADE (petabytes) | GLADE |

| Best for | Development, small runs | Batch jobs | Large climate simulations | Data analysis, ML |

When you’ve outgrown your laptop:

- Ensemble with 1000+ members

- Processing 10+ TB of climate data

- Simulations that run for hours even parallelized

- Need more RAM than your laptop has

The code you write today (ProcessPoolExecutor, Dask) scales directly to HPC — you just request more cores in your job script.

Summary

Key Takeaways

The GIL prevents Python threads from running CPU-bound code in parallel — use processes instead

Vectorize first — replacing loops with NumPy/xarray operations is the easiest and often biggest speedup

multiprocessing.Pool.map()andProcessPoolExecutorrun independent tasks on separate CPU coresconcurrent.futures is the modern, preferred API — swap

Process↔︎Threadwith one wordDask extends parallelism to larger-than-memory datasets and integrates seamlessly with xarray

Always profile before parallelizing — the overhead of spawning processes can exceed the speedup for small tasks

Cheat Sheet

Vectorization:

multiprocessing:

concurrent.futures:

Dask + xarray:

Always remember:

Looking Ahead

Next lectures:

- Week 10: More advanced topics

- Building toward your final projects

This week’s lab:

- Apply

ProcessPoolExecutorto a real data-processing task - Compare serial vs. vectorized vs. parallel timings

- Write a short report on when each approach is best

Pro tip: Start with the serial version. Get it working correctly. THEN parallelize. Debugging parallel code is much harder than debugging serial code.

Questions?

Key things to remember:

- Vectorize first, parallelize second

ProcessPoolExecutorfor CPU-bound tasksThreadPoolExecutorfor I/O-bound tasks- Dask for larger-than-memory xarray workflows

- Always use the

if __name__ == "__main__":guard

The speed landscape in one sentence: Vectorize your arrays, parallelize your tasks, and let Dask handle the rest.

Contact

Prof. Will Chapman

wchapman@colorado.edu

willychap.github.io

ATOC Building, CU Boulder

See you next week!

ATOC 4815/5815 - Week 9