pi = 3.1416

sqrt(2) = 1.4142

e = 2.7183ATOC 4815/5815

Linking Python Scripts Together - Week 5.5

CU Boulder ATOC

Spring 2026

Linking Python Scripts Together

Today’s Objectives

- Understand why we split code across multiple

.pyfiles - Import functions and classes from your own scripts

- Master the

if __name__ == "__main__"guard - Organize a small project into reusable modules

Reminders

Midterm Grades Posted!

- Check Canvas for scores and feedback

- Office hours this week for questions

Office Hours:

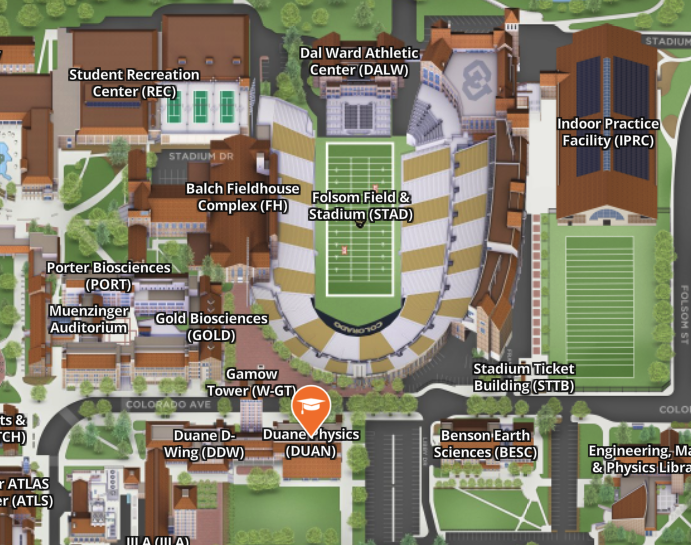

Will: Tu 11:15-12:15p Th 9-10a Aerospace Cafe

Aiden: M / W 330-430p DUAN D319

ATOC 4815/5815 Playlist

ATOC 4815/5815 Playlist

Spotify Playlist: ATOC4815

- This Lecture:

Hot Chip - Ready for the Fall / I Feel Better

- here → playlist

Why Multiple Files?

The One-Giant-Notebook Problem

You’ve been writing everything in one notebook or one script. That works at first…

But then a .py for our Lorenz system looks like this:

lorenz63_everything.py (400 lines)

├── import statements

├── Lorenz63 class

├── plotting functions

├── utility helpers

├── analysis code

└── if __name__ == "__main__": ... (maybe)Problems:

- Hard to find anything — scroll, scroll, scroll…

- Can’t reuse your

Lorenz63class in a new analysis without copy-pasting - One typo can break everything

- Collaborators can’t work on different parts at the same time

The Solution: Split Into Modules

A module is just a .py file that contains functions, classes, or variables.

my_project/

├── lorenz63.py ← the Lorenz63 class

├── plotting.py ← plotting helper functions

├── utils.py ← small utility functions

└── run_experiment.py ← the main script that ties it all togetherBenefits:

- Each file has one job (single responsibility)

- Reuse

lorenz63.pyin any future project - Easier to read, test, and debug

- Multiple people can work on different files

You already do this! Every time you write import numpy, you’re importing a module someone else wrote.

Importing Your Own Code

Review: Importing Built-In Modules

You’ve been doing this since week 1:

The same syntax works for your own .py files!

Importing From Your Own File

Step 1: Write a file called conversions.py:

Three Import Styles

All three work. Each has trade-offs:

Import the module:

Verbose but clear where things come from.

Import specific names:

Shorter. You see exactly what you use.

General Rule: Use from module import name1, name2 for most cases. Use import module when you use many things from it (like numpy).

Common Error: ModuleNotFoundError

Predict the output:

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'conversions'Why? Python can’t find conversions.py. Most common causes:

| Cause | Fix |

|---|---|

| File doesn’t exist | Create conversions.py |

| File is in a different folder | Move it, or adjust sys.path |

| Typo in the name | import conveRsions vs import conversions |

| Running from wrong directory | cd to the project folder first |

Check Your Understanding

Given this project layout:

weather_project/

├── conversions.py ← has celsius_to_fahrenheit()

├── analysis.py ← your main script

└── data/

└── temps.csvWhich import works in analysis.py?

Answer: Option A

- A works because

conversions.pyis in the same folder asanalysis.py - B would work if you’re running from outside

weather_project/and it’s a package - C is wrong — you import modules (files), not functions directly

The __name__ Guard

The Problem: Code That Runs on Import

Imagine conversions.py has some test code at the bottom:

# conversions.py

def celsius_to_fahrenheit(temp_c):

return temp_c * 9/5 + 32

def fahrenheit_to_celsius(temp_f):

return (temp_f - 32) * 5/9

# Quick test

print("Testing conversions...")

print(f"0°C = {celsius_to_fahrenheit(0)}°F")

print(f"100°C = {celsius_to_fahrenheit(100)}°F")

print("All tests passed!")Why Does This Happen?

Key insight: When Python imports a .py file, it executes the entire file from top to bottom.

- Function/class definitions → stored for later use (good!)

- Any code at the top level → runs immediately (often bad!)

import conversions

│

├─ def celsius_to_fahrenheit(...) ← defined, stored ✓

├─ def fahrenheit_to_celsius(...) ← defined, stored ✓

├─ print("Testing conversions...") ← RUNS immediately ✗

├─ print(f"0°C = ...") ← RUNS immediately ✗

└─ print("All tests passed!") ← RUNS immediately ✗This is why we need the __name__ guard.

The __name__ Variable

Every Python file has a built-in variable called __name__.

It has two possible values:

| Situation | __name__ equals |

|---|---|

You run the file directly: python my_file.py |

"__main__" |

Someone imports the file: import my_file |

"my_file" |

Demo:

This is how a file knows whether it’s being run or imported!

The Guard Pattern

Wrap any “run only when executed directly” code in this block:

# conversions.py

def celsius_to_fahrenheit(temp_c):

return temp_c * 9/5 + 32

def fahrenheit_to_celsius(temp_f):

return (temp_f - 32) * 5/9

if __name__ == "__main__":

# This only runs when you do: python conversions.py

print("Testing conversions...")

print(f"0°C = {celsius_to_fahrenheit(0)}°F")

print(f"100°C = {celsius_to_fahrenheit(100)}°F")

print("All tests passed!")Now:

| Action | What happens |

|---|---|

python conversions.py |

Functions defined + tests run |

from conversions import celsius_to_fahrenheit |

Functions defined, tests skipped |

Common Error: Forgetting the Guard

Predict what happens:

# euler.py

import numpy as np

class Lorenz63:

def __init__(self, sigma=10, rho=28, beta=8/3, dt=0.01):

self.sigma, self.rho, self.beta, self.dt = sigma, rho, beta, dt

def tendency(self, state):

x, y, z = state

return np.array([self.sigma*(y-x), self.rho*x - y - x*z, x*y - self.beta*z])

def step(self, state):

return state + self.tendency(state) * self.dt

# "Quick test" without guard

model = Lorenz63()

state = np.array([1.0, 1.0, 1.0])

for _ in range(1000):

state = model.step(state)

print(f"Final state: {state}")Check Your Understanding

Which version is correct?

Version A:

Answer: Version B

- Version A:

from stats import anomalywould print output every time - Version B:

from stats import anomalyjust gives you the function, cleanly - Version B still works as a standalone script:

python stats.pyruns the test

Building a Real Project

Project Structure: Weather Toolkit

Let’s build a small multi-file project step by step:

weather_toolkit/

├── conversions.py ← temperature unit conversions

├── stats.py ← statistical analysis functions

├── plotting.py ← visualization helpers

└── run_analysis.py ← main script that ties it all togetherDesign principle: Each file has one job.

| File | Responsibility |

|---|---|

conversions.py |

Unit conversions (C↔︎F↔︎K) |

stats.py |

Anomalies, climatology, running mean |

plotting.py |

Standard plot templates for the course |

run_analysis.py |

Load data, call functions, produce output |

This is how python software code is organized — the same pattern scales from homework to research.

Step 1: conversions.py

# conversions.py

"""Temperature unit conversion utilities."""

def celsius_to_fahrenheit(temp_c):

"""Convert Celsius to Fahrenheit."""

return temp_c * 9/5 + 32

def celsius_to_kelvin(temp_c):

"""Convert Celsius to Kelvin."""

return temp_c + 273.15

def wind_speed_knots_to_ms(knots):

"""Convert wind speed from knots to m/s."""

return knots * 0.514444

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Quick sanity checks

assert celsius_to_fahrenheit(0) == 32

assert celsius_to_fahrenheit(100) == 212

assert celsius_to_kelvin(0) == 273.15

print("conversions.py: all checks passed")Notice:

- Docstrings on every function (good practice!)

if __name__guard withassertstatements for self-testing- Running

python conversions.pyverifies the module works

Step 2: stats.py

# stats.py

"""Statistical analysis functions for atmospheric data."""

import numpy as np

def compute_anomaly(data, axis=None):

"""Subtract the mean to get anomalies."""

climatology = data.mean(axis=axis, keepdims=True)

return data - climatology

def running_mean(data, window):

"""Compute running mean with given window size."""

kernel = np.ones(window) / window

return np.convolve(data, kernel, mode='valid')

def find_extremes(data):

"""Return dict with min, max, and their indices."""

return {

'min_val': data.min(),

'max_val': data.max(),

'min_idx': data.argmin(),

'max_idx': data.argmax(),

}

if __name__ == "__main__":

test_data = np.array([1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0])

anom = compute_anomaly(test_data)

assert np.isclose(anom.mean(), 0.0)

print("stats.py: all checks passed")Step 3: plotting.py

# plotting.py

"""Standard plotting templates for ATOC 4815."""

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def plot_timeseries(time, data, ylabel, title, label=None, ax=None):

"""Create a labeled time series plot."""

if ax is None:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(9, 4))

ax.plot(time, data, linewidth=2, label=label)

ax.set_xlabel('Time')

ax.set_ylabel(ylabel)

ax.set_title(title)

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

if label:

ax.legend()

return ax

def plot_comparison(time, datasets, labels, ylabel, title):

"""Plot multiple time series on the same axes."""

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(9, 4))

for data, label in zip(datasets, labels):

ax.plot(time, data, linewidth=2, label=label)

ax.set_xlabel('Time')

ax.set_ylabel(ylabel)

ax.set_title(title)

ax.legend()

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

return fig, ax

if __name__ == "__main__":

import numpy as np

t = np.linspace(0, 24, 100)

y = 15 + 8 * np.sin(t * np.pi / 12)

plot_timeseries(t, y, 'Temp (°C)', 'Test Plot')

plt.show()

print("plotting.py: visual check passed")Step 4: run_analysis.py

# run_analysis.py

"""Main analysis script — ties all modules together."""

import numpy as np

from conversions import celsius_to_fahrenheit

from stats import compute_anomaly, running_mean, find_extremes

from plotting import plot_timeseries, plot_comparison

# --- Generate synthetic data ---

np.random.seed(42)

hours = np.arange(0, 72) # 3 days

temp_c = 15 + 8 * np.sin((hours - 6) * np.pi / 12) + np.random.randn(72) * 2

# --- Analysis ---

temp_f = celsius_to_fahrenheit(temp_c)

anomalies = compute_anomaly(temp_c)

smooth = running_mean(temp_c, window=6)

extremes = find_extremes(temp_c)

print(f"Max temp: {extremes['max_val']:.1f}°C at hour {extremes['max_idx']}")

print(f"Min temp: {extremes['min_val']:.1f}°C at hour {extremes['min_idx']}")

# --- Visualization ---

plot_comparison(

hours,

[temp_c, np.pad(smooth, (2, 3), constant_values=np.nan)],

['Raw', '6-hr Running Mean'],

'Temperature (°C)',

'72-Hour Boulder Temperature Analysis'

)

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.savefig('boulder_analysis.png', dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

print("Analysis complete!")Look how clean this is! The main script reads almost like English because each function has a clear name and lives in a focused module.

The Import Flow

When you run python run_analysis.py, here’s what happens:

python run_analysis.py

│

├─ import numpy as np ← from installed packages

├─ from conversions import celsius_to_fahrenheit

│ └─ Python executes conversions.py

│ ├─ defines celsius_to_fahrenheit ← kept ✓

│ ├─ defines celsius_to_kelvin ← kept (not imported, but defined)

│ └─ if __name__ == "__main__": ... ← SKIPPED (name is "conversions")

├─ from stats import compute_anomaly, ...

│ └─ Python executes stats.py

│ ├─ import numpy as np ← numpy loaded (cached)

│ ├─ defines compute_anomaly ← kept ✓

│ └─ if __name__ == "__main__": ... ← SKIPPED

├─ from plotting import ...

│ └─ ...same pattern...

│

└─ Your analysis code runsEvery imported file is executed once, top to bottom. The __name__ guard prevents side effects.

Import Pitfalls

Circular Imports

What happens here?

ImportError: cannot import name 'get_temp' from partially initialized

module 'temperature' (most likely due to a circular import)What went wrong?

- Python starts loading

wind.py - Line 1:

from temperature import get_temp→ Python pauseswind.pyand starts loadingtemperature.py - Line 1 of

temperature.py:from wind import wind_chill→ butwind.pyisn’t done yet! wind_chilldoesn’t exist yet → crash

Fixing Circular Imports

The rule: import dependencies must flow one way — like a river, not a loop.

Before (broken): each file imports from the other

wind.py ──imports──▶ temperature.py

▲ │

└────────imports─────────┘ ← CYCLE!After (fixed): extract the shared piece into a third file

core.py ◀── wind.py ◀── temperature.py ← one direction, no cycle ✓Import Order Convention

PEP 8 (the Python style guide) recommends this order:

Why?

- Separates “always available” from “need to install” from “our code”

- Makes it easy to see dependencies at a glance

- Most linters (like

flake8) will warn if you mix them up

Simple rule: stdlib → third-party → yours, with a blank line between each group.

Common Error: Shadowing Module Names

Predict the output:

AttributeError: module 'math' has no attribute 'sqrt'Why? Python found your math.py before the built-in math module!

Dangerous file names to avoid:

| Don’t name your file | It shadows |

|---|---|

math.py |

import math |

random.py |

import random |

numpy.py |

import numpy |

test.py |

import test (built-in) |

statistics.py |

import statistics |

Fix: Rename your file to something specific: my_math_utils.py, weather_stats.py, etc.

The __init__.py File

When your Python project grows beyond loose .py files into an organized folder, you’ll see a special file called __init__.py. What does it do, and when do you actually need it?

“Wait, I can already import files without this…” — Yes! If you’re inside a folder, Python finds sibling files automatically:

But when you use dot notation to reach into a folder from outside, Python needs __init__.py:

lorenz_project/

├── __init__.py ← without this: ModuleNotFoundError

├── integrators.py

├── lorenz63.py

└── plotting.pyWithout __init__.py:

With __init__.py (even empty):

Rule: __init__.py is needed when you reference a folder with dot notation — i.e., when you treat it as a package rather than just a directory you happen to be sitting in.

__init__.py — More Than Just Empty

An empty __init__.py is fine to start, but it can also do useful things:

1. Convenience imports — let users skip the submodule path:

Now instead of the long path:

users can just write:

2. Package-level metadata:

3. Control what from package import * exports:

For this lab: an empty __init__.py is all you need. But as your projects grow, this file becomes your package’s front door.

Lab: Lorenz63 Ensemble Experiment

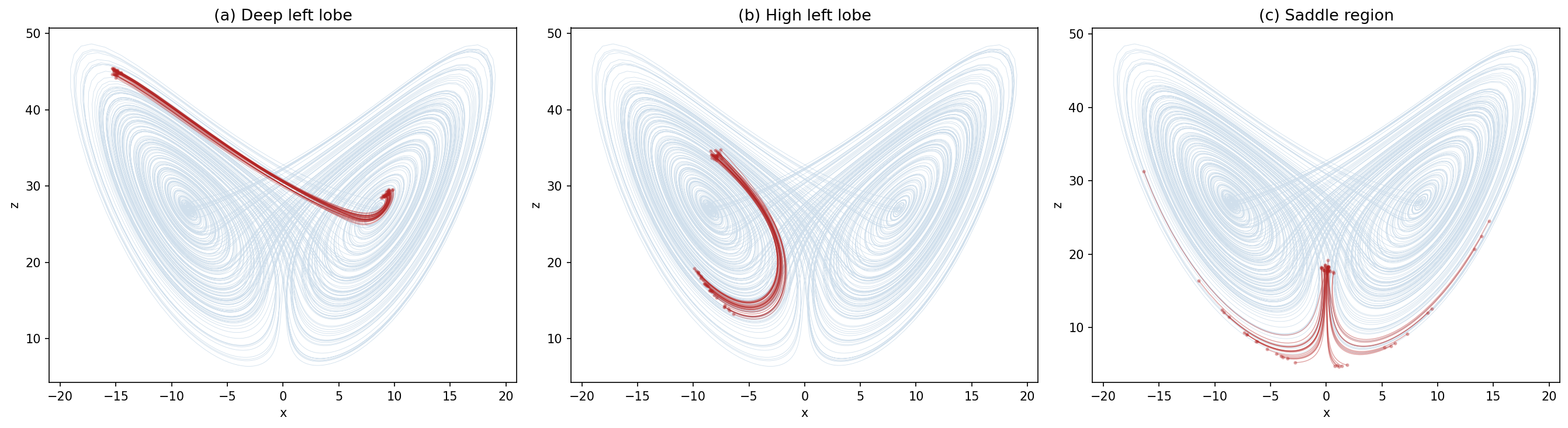

Predictability Depends on Location

The Lorenz attractor has regions where forecasts stay accurate and regions where they immediately diverge.

Your goal: Build a multi-file project that produces this figure:

Three panels showing ensembles of trajectories started from different regions of the attractor:

| Panel | Starting region | What you’ll see |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Deep left lobe [-15,1,45] | Deep in the left wing | Ring of uncertainty barely grows — highly predictable |

| (b) High left lobe [-8,-3,34] | Upper part of left wing, near transition | ensemble slightly diverves - ** medium predictability ** |

| (c) Saddle region [0,0,18] | Between the two wings | Ensemble explodes — some go left, some go right — no predictability |

This is the key insight of chaos: not all regions of a system are equally predictable. Weather models face exactly this challenge.

Your Project Structure

Refactor your midterm code into this multi-file project:

lorenz_project/

├── __init__.py ← empty, makes this a package

├── integrators.py ← euler_step() and integrate()

├── lorenz63.py ← Lorenz63 class with run() and run_ensemble()

├── plotting.py ← plot_attractor(), plot_ensemble(), plot_ensemble_panels()

└── run_lorenz_ensemble.py ← driver script — produces the 3-panel figureWho imports whom? Read each arrow as “imports from”:

run_lorenz_ensemble.py

├── imports from ──▶ lorenz63.py

│ └── imports from ──▶ integrators.py

└── imports from ──▶ plotting.pyNotice: arrows only point downward/right — no file imports from a file that imports it back. That’s what “no circular imports” means.

Starter files are provided — each has docstrings, hints, and TODO markers. Fill them in.

File 1: integrators.py

What to implement:

| Function | Signature | What it does |

|---|---|---|

euler_step |

(state, tendency_fn, dt) → state |

One Forward Euler step |

integrate |

(state0, tendency_fn, dt, n_steps) → trajectory |

Full time loop, returns shape (n_steps+1, n_vars) |

File 2: lorenz63.py

What to implement:

| Method | What it does |

|---|---|

__init__(sigma, rho, beta) |

Store parameters |

tendency(state) |

Return \([dx/dt,\; dy/dt,\; dz/dt]\) |

run(state0, dt, n_steps) |

Integrate one trajectory (calls integrate from integrators.py) |

run_ensemble(ics, dt, n_steps) |

Integrate many trajectories from an array of initial conditions |

The ensemble method — implement it two ways:

- Nested for loop: loop over members, call

self.run()for each one - Vectorized: single loop over time steps, advance all members at once

# Method 1: loop over members (straightforward)

for i in range(n_members):

ensemble[i] = self.run(ics[i], dt, n_steps)

# Method 2: loop over time only (fast!)

# states shape: (n_members, 3) — all members at once

for t in range(n_steps):

states = states + vectorized_tendency(states) * dtFile 3: plotting.py

What to implement:

| Function | What it does |

|---|---|

plot_attractor(ax, trajectory) |

Plot one trajectory in \(x\)-\(z\) phase space (the butterfly) |

plot_ensemble(ax, ensemble, reference) |

Plot reference attractor (light) + ensemble members (bold) |

plot_ensemble_panels(ensemble_list, reference, titles) |

Create the 3-panel figure, one panel per starting region |

Plotting tips:

- Use

trajectory[:, 0]for \(x\) andtrajectory[:, 2]for \(z\) - Reference attractor: light color, low alpha (

alpha=0.3) - Ensemble members: bold color like

"firebrick", higher alpha plt.savefig(path, dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')to save

File 4: run_lorenz_ensemble.py

The driver script. This ties everything together:

- Create a

Lorenz63model with default parameters - Spin up a reference trajectory (2000 steps to get on the attractor, then 10000 more)

- Pick 3 starting points from the reference — one in each region:

- Deep left lobe: find a point where \(x < -10\) and \(z < 25\)

- High left lobe: find a point where \(x < -5\) and \(z > 35\)

- Saddle: find a point where \(|x| < 2\)

- For each starting point, create ~30 nearby initial conditions by adding small perturbations (

np.random.randn(30, 3) * 0.5) - Run

model.run_ensemble()for each cloud - Call

plot_ensemble_panels()to make the 3-panel figure - Save to

lorenz_ensemble_predictability.png

Deliverables Checklist

integrators.py— runpython -m lorenz_project.integratorsand confirm it prints"all checks passed!"(tests Euler on \(dy/dt = -y\), checks answer ≈ \(e^{-1}\))lorenz63.py— runpython -m lorenz_project.lorenz63and confirm it prints"all checks passed!"(checks trajectory shape is(1001, 3)and ensemble shape is(5, 1001, 3))plotting.py— runpython -m lorenz_project.plotting— a plot window should appear with a random-walk line. If you see a line, it works.run_lorenz_ensemble.py— runpython -m lorenz_project.run_lorenz_ensemble— produces and saveslorenz_ensemble_predictability.png- Every file has an

if __name__ == "__main__":guard with tests inside it run_ensembleimplemented with Method 1 (nested loop); Method 2 (vectorized) for bonus- The figure —

lorenz_ensemble_predictability.pngwith three panels showing how predictability varies across the attractor

Grading:

- Working multi-file structure with correct imports: 40%

- Ensemble method (Method 1): 30%

- Final 3-panel figure: 20%

- Vectorized ensemble (Method 2, bonus): 10%

What You’ll Discover

When your figure is done, you’ll see:

(a) Deep left lobe — The ensemble starts tight and stays together. Trajectories orbit the left wing in sync. The ring of uncertainty barely grows. Highly predictable.

(b) High left lobe — The ensemble starts tight but distorts. Some members continue looping left, others begin transitioning to the right lobe. The ring stretches into banana and boomerang shapes. Partially predictable — you know roughly where, but not which lobe.

(c) Saddle region — The ensemble starts tight but immediately explodes. Some trajectories go left, some go right. This is where the two wings meet and tiny differences get maximally amplified. No predictability.

This is exactly the problem weather forecasters face: some atmospheric states are inherently more predictable than others. Ensemble forecasting reveals where confidence is warranted and where it isn’t.

Summary

Key Takeaways

Split code into modules — each

.pyfile should have one clear jobImport styles:

import module→module.function()(explicit)from module import function→function()(convenient)from module import *→ avoid (namespace pollution)

Always use

if __name__ == "__main__":to guard code that should only run when the file is executed directlyAvoid pitfalls:

- Don’t name files after built-in modules

- Keep import dependencies one-directional (no circular imports)

- Follow PEP 8 import ordering: stdlib → third-party → local

This pattern scales — from homework to research code to production software

The __name__ Guard Cheat Sheet

# my_module.py

# --- Imports at the top ---

import numpy as np

# --- Functions and classes ---

def my_function():

...

class MyClass:

...

# --- Guard: only runs when executed directly ---

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Tests, demos, or standalone behavior

result = my_function()

print(f"Self-test: {result}")Memorize this template. Every .py file you write for this course (and beyond) should follow it.

Looking Ahead

Next lectures:

- Week 6: Git for scientists — version control your projects

- Week 7: Tabular data with Pandas

This week’s lab:

- Complete the

lorenz_project/files - Produce the 3-panel ensemble predictability figure

- Submit: all

.pyfiles + the saved figure

Pro tip: Build and test one file at a time. Run each self-test before moving to the next file.

Questions?

Key things to remember:

- A module is just a

.pyfile importexecutes the file,__name__controls what runs- One-way dependencies, no circles

- Build bottom-up:

integrators→lorenz63→plotting→run_lorenz_ensemble

You already wrote all the hard code for the midterm. Now you’re organizing it and extending it.

Contact

Will Chapman

wchapman@colorado.edu

willychap.github.io

SEEC Building N258, CU Boulder

See you next week!

ATOC 4815/5815 - Week 5.5