Why NumPy?

Big Idea: NumPy arrays let us do math on whole datasets at once , instead of writing slow Python loops.

Pure Python list:

= [15.2 , 18.7 , 22.1 , 19.8 ]= []for t in temps:* 9 / 5 + 32 )

Loop in Python

Manual append logic

Harder to read and optimize

NumPy array:

= np.array([15.2 , 18.7 , 22.1 , 19.8 ])= temps * 9 / 5 + 32

One line does the math for all elements

Operations implemented in fast C code

Reads like the mathematical formula

Arrays: fixed-size, typed, efficient blocks of numbers

NumPy lets you:

Apply operations to entire arrays (vectorize)

Avoid many explicit loops

Write shorter, clearer, and usually much faster numerical code

Common Error: Forgetting to Import

Predict the output:

= np.array([15.2 , 18.7 , 22.1 ])print (temps)

NameError: name 'np' is not definedThe Fix:

import numpy as np # ALWAYS at the top of your file = np.array([15.2 , 18.7 , 22.1 ])print (temps)

Takeaway: import numpy as np is the standard convention. Put all imports at the top of your script/notebook.

Creating Arrays

Big Idea: Use NumPy’s constructors to quickly build arrays for real data, ranges, and constant grids.

import numpy as np# From existing list = np.array([15.2 , 18.7 , 22.1 ])print (f"From list: { temps} " )# Range-like sequence = np.arange(0 , 10 , 2 )print (f"arange: { indices} " )# Evenly spaced samples = np.linspace(0 , 1 , 5 )print (f"linspace: { samples} " )

From list: [15.2 18.7 22.1]

arange: [0 2 4 6 8]

linspace: [0. 0.25 0.5 0.75 1. ]

# Constant arrays = np.zeros(3 )print (f"zeros: { zeros} " )= np.ones(3 )print (f"ones: { ones} " )= np.full(3 , 20.5 )print (f"full: { filled} " )

zeros: [0. 0. 0.]

ones: [1. 1. 1.]

full: [20.5 20.5 20.5]

Takeaway:

np.array for real data you already havearange / linspace for ranges and sample points zeros / full for constant grids you will use in calculations

Check Your Understanding 🤔

What’s the difference between arange and linspace?

= np.arange(0 , 10 , 2 )= np.linspace(0 , 10 , 5 )

Answer:

arange(start, stop, step): goes from 0 to 10 by steps of 2 → [0, 2, 4, 6, 8]linspace(start, stop, num): 5 evenly spaced points from 0 to 10 → [0., 2.5, 5., 7.5, 10.]

Key difference: arange uses step size , linspace uses number of points and includes the endpoint!

When to use which?

arange: When you know the step (e.g., hourly data, every 5 km)linspace: When you need exact number of samples (e.g., 100 points for smooth plot)

Common Error: Integer Division

Predict the output:

= np.array([20 , 25 , 30 ]) # integers! = temps_c * 9 / 5 + 32 print (f"Result: { temps_f} " )print (f"dtype: { temps_f. dtype} " )

Result: [68. 77. 86.]

dtype: float64

Wait, this worked! Why?

In Python 3, / always returns float. But watch out for this:

= np.array([20 , 25 , 30 ])# Using integer division by mistake = temps_c // 5 # // is integer division! print (f"Wrong: { result} " )

Takeaway: Be mindful of your dtypes. When in doubt, create float arrays: np.array([20.0, 25.0, 30.0]) or temps_c.astype(float)

Array Attributes: dtype, shape, ndim

Big Idea: Check an array’s dtype, shape, and ndim early. It saves you from weird bugs later.

# 1-D array = np.array([15.2 , 18.7 , 22.1 ])print (f"dtype: { temps. dtype} " )print (f"shape: { temps. shape} " )print (f"ndim: { temps. ndim} " )

dtype: float64

shape: (3,)

ndim: 1

# 2-D array = np.array([[1 , 2 , 3 ], [4 , 5 , 6 ]])print (f"dtype: { data. dtype} " )print (f"shape: { data. shape} " )print (f"ndim: { data. ndim} " )

dtype: int64

shape: (2, 3)

ndim: 2

dtype – data type of the array

e.g. float64, int32, bool

Watch out if you accidentally create int when you want float

shape – size of the array in each dimension

1-D: (5,) (5 elements)

2-D: (2,3) (2 rows, 3 columns)

ndim – number of dimensions

1-D vector: ndim == 1

2-D matrix: ndim == 2

When something crashes or broadcasts strangely, first print:

array.dtype, array.shape, array.ndim

Visual: Understanding Shape

1-D array: shape = (5,)

────────────────────────────────────────

[15.2, 18.7, 22.1, 19.8, 16.5]

↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑

idx 0 1 2 3 4

2-D array: shape = (3, 4) means 3 rows, 4 columns

────────────────────────────────────────

Col 0 Col 1 Col 2 Col 3

Row 0 [ 15 18 22 19 ]

Row 1 [ 14 17 21 18 ]

Row 2 [ 16 19 23 20 ]

↑

First index = row

Second index = column

Atmospheric example: 10 stations, 24 hours

────────────────────────────────────────

shape = (10, 24)

↑ ↑

stations hours

Key concepts:

1-D array: shape = (5,) → 5 elements in a line2-D array: shape = (3, 4) → 3 rows, 4 columnsThink: “rows first, then columns” (like matrix notation)Stations × Time: If you have 10 stations and 24 hours, shape is (10, 24)

Check Your Understanding 🤔

What will be the shape?

# 5 weather stations, 48 hours of data each = np.random.randn(5 , 48 )

Answer: shape = (5, 48)

First dimension: 5 stations

Second dimension: 48 hours

Total elements: 5 × 48 = 240

Now predict: What’s the shape of temps[0, :]?

(48,) — a 1-D array of 48 hours for station 0

Indexing and Slicing

Big Idea: NumPy indexing feels like list indexing, but works in multiple dimensions and stays fast.

1-D arrays:

= np.array([15.2 , 18.7 , 22.1 , 19.8 , 16.5 ])# Single element print (f"First: { temps[0 ]} " )print (f"Last: { temps[- 1 ]} " )# Slicing print (f"First 3: { temps[:3 ]} " )print (f"Last 2: { temps[- 2 :]} " )print (f"Every other: { temps[::2 ]} " )

First: 15.2

Last: 16.5

First 3: [15.2 18.7 22.1]

Last 2: [19.8 16.5]

Every other: [15.2 22.1 16.5]

N-D arrays:

= np.array([[1 , 2 , 3 ],4 , 5 , 6 ]])# Single element print (f"Row 0, Col 1: { data[0 , 1 ]} " )# Slicing print (f"First row: { data[0 , :]} " )print (f"Second column: \n { data[:, 1 ]} " )

Row 0, Col 1: 2

First row: [1 2 3]

Second column:

[2 5]

Key points:

1-D: temps[start:stop:step] just like lists

N-D: array[row_index, col_index] and array[row_slice, col_slice]

Slices are views into the original data (no copy in most cases)

Common Error: Wrong Dimension Indexing

Predict the output:

= np.array([[1 , 2 , 3 ],4 , 5 , 6 ]])print (data[1 ]) # What does this return? print (data[:, 1 ]) # What about this?

= np.array([[1 , 2 , 3 ], [4 , 5 , 6 ]])print (f"data[1]: { data[1 ]} " ) # Second ROW print (f"data[:, 1]: { data[:, 1 ]} " ) # Second COLUMN

data[1]: [4 5 6]

data[:, 1]: [2 5]

Common mistake: Forgetting that data[1] gives you a row , not a column!

To get a column, you need data[:, 1] (all rows, column 1)

Boolean Masks

Big Idea: Comparisons create boolean arrays that you can use to filter values. Masks replace manual if loops.

= np.array([15.2 , 18.7 , 22.1 , 19.8 , 16.5 ])# Create boolean mask = (temps >= 15 ) & (temps <= 22 )print (f"Mask: { mask} " )# Filter using mask = temps[mask]print (f"Comfortable temps: { comfortable_temps} " )

Mask: [ True True False True True]

Comfortable temps: [15.2 18.7 19.8 16.5]

# Count how many meet condition = np.sum (mask)print (f"Number of comfortable temps: { count} " )

Number of comfortable temps: 4

Takeaway:

(temps >= 15) returns a boolean array& combines conditions elementwise (use &, not and!)temps[mask] selects only the elements where mask is TrueInstead of looping and if, build a mask once and index with it

Try It Yourself 💻

Challenge: Given this temperature data, find:

All temperatures above 20°C

How many hours were between 15-25°C

The indices where temp > 22°C (hint: np.where)

= np.array([...]) # 24 hours of data

Solution:

# 1. Temps above 20 = hourly_temps[hourly_temps > 20 ]print (f"Hot hours: { hot[:5 ]} ..." ) # show first 5 # 2. Count between 15-25 = np.sum ((hourly_temps >= 15 ) & (hourly_temps <= 25 ))print (f"Comfortable hours: { comfortable} " )# 3. Indices where > 22 = np.where(hourly_temps > 22 )[0 ]print (f"Hot hour indices: { indices} " )

Hot hours: [21.89329683 24.70023953 21.97111934 22.42714652 26.14676948]...

Comfortable hours: 15

Hot hour indices: [3 5 6 7 9]

Common Error: Using ‘and’ Instead of ‘&’

Predict the output:

= np.array([15.2 , 18.7 , 22.1 , 19.8 , 16.5 ])= (temps >= 15 ) and (temps <= 22 ) # Wrong!

ValueError: The truth value of an array with more than one element is ambiguous.The Fix:

= np.array([15.2 , 18.7 , 22.1 , 19.8 , 16.5 ])= (temps >= 15 ) & (temps <= 22 ) # Correct! print (f"Mask: { mask} " )

Mask: [ True True False True True]

Why?

and is for single boolean values: True and False& is for element-wise array operationsAlways use & (and | for OR) with NumPy arrays Don’t forget parentheses: (temps >= 15) & (temps <= 22)

Vectorized Operations & Broadcasting

Big Idea: NumPy applies the same formula to whole arrays at once. Scalars and smaller arrays are broadcast to match shapes.

= np.array([15.2 , 18.7 , 22.1 , 19.8 ])# Convert to Fahrenheit = temps * 9 / 5 + 32 print (f"°F: { temp_f} " )# Subtract baseline = 15 = temps - baselineprint (f"Anomaly: { anomaly} " )

°F: [59.36 65.66 71.78 67.64]

Anomaly: [0.2 3.7 7.1 4.8]

# Element-wise operations = temps ** 2 print (f"Squared: { temps_squared} " )# Works with functions too = np.round (temps, 1 )print (f"Rounded: { temps_rounded} " )

Squared: [231.04 349.69 488.41 392.04]

Rounded: [15.2 18.7 22.1 19.8]

Key concepts:

Arithmetic (+, -, *, /, **) is elementwise on arrays

Scalars are broadcast automatically to match array shape

You write the math once; NumPy handles the loops in fast C code

Think in formulas on arrays, not in explicit Python for loops

Common Error: Shape Mismatch

Predict the output:

= np.array([15 , 20 , 25 , 30 ]) # shape (4,) = np.array([5 , 10 , 15 ]) # shape (3,) = temps + wind

ValueError: operands could not be broadcast together with shapes (4,) (3,)Why? Arrays must have compatible shapes for broadcasting!

Debugging strategy:

= np.array([15 , 20 , 25 , 30 ])= np.array([5 , 10 , 15 ])print (f"temps.shape: { temps. shape} " )print (f"wind.shape: { wind. shape} " )# They must match or one must be 1!

temps.shape: (4,)

wind.shape: (3,)

The fix: Make sure your arrays have the same length, or reshape one of them

Array Statistics

Big Idea: NumPy has built-in “reductions” (mean, std, min, max, etc.) that keep your analysis code short and clear.

Full array:

= np.array([15.2 , 18.7 , 22.1 , 19.8 , 16.5 ])print (f"Mean: { temps. mean():.1f} " )print (f"Std: { temps. std():.1f} " )print (f"Min: { temps. min ():.1f} " )print (f"Max: { temps. max ():.1f} " )print (f"Sum: { temps. sum ():.1f} " )

Mean: 18.5

Std: 2.4

Min: 15.2

Max: 22.1

Sum: 92.3

Axis example:

# 2D array: 3 stations, 4 times = np.array([[15 , 18 , 22 , 19 ],14 , 17 , 21 , 18 ],16 , 19 , 23 , 20 ]])# Mean across time (axis=1) = data.mean(axis= 1 )print (f"Station means: { station_means} " )# Mean across stations (axis=0) = data.mean(axis= 0 )print (f"Time means: { time_means} " )

Station means: [18.5 17.5 19.5]

Time means: [15. 18. 22. 19.]

Key points:

Reductions turn many values → one (or one per row/column)

axis=None (default) flattens everythingaxis=0 works “down” rows, axis=1 works “across” columnsUsing these methods avoids writing your own loops and counters

Visual: Understanding axis=0 vs axis=1

data = [[15, 18, 22, 19], shape (3, 4)

[14, 17, 21, 18], 3 stations (rows)

[16, 19, 23, 20]] 4 times (columns)

axis=0: collapse ROWS (↓) axis=1: collapse COLUMNS (→)

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ → → → →

[15, 18, 22, 19] [18.5] ← mean of row 0

[17.5] ← mean of row 1

Result: (4,) [19.5] ← mean of row 2

mean per TIME Result: (3,)

mean per STATION

Mnemonic: axis=0 → “collapse dimension 0 (rows)”

axis=1 → “collapse dimension 1 (columns)”

Check Your Understanding 🤔

Given this data:

# 4 stations, 24 hours = np.random.randn(4 , 24 ) * 5 + 20 print (f"Shape: { temps. shape} " )

What will be the shape of:

temps.mean(axis=0)temps.mean(axis=1)temps.mean()

Answers:

(24,) — mean across stations, one value per hour(4,) — mean across time, one value per stationScalar — mean of all values (flattened)

Common Error: Wrong Axis

Scenario: You want the mean temperature for each station (averaged over time)

# 4 stations, 24 hours of data = np.random.randn(4 , 24 ) * 5 + 20 # Which is correct? = temps.mean(axis= 0 )= temps.mean(axis= 1 )

Answer: temps.mean(axis=1)

= np.random.randn(4 , 24 ) * 5 + 20 = temps.mean(axis= 1 )print (f"Shape: { station_means. shape} " ) # (4,) ✓ print (f"Station means: { station_means} " )

Shape: (4,)

Station means: [19.55167332 21.05860409 20.14683389 21.58417493]

Why? axis=1 collapses the time dimension, leaving station dimension

Strategy: Always check the output shape! It should match what you expect.

Try It Yourself 💻

Challenge: Given temperature and wind speed data:

Calculate wind chill: WC = 13.12 + 0.6215*T - 11.37*V^0.16 + 0.3965*T*V^0.16 (T = temp in °C, V = wind speed in km/h)

Find how many hours have wind chill below 0°C

Calculate the mean and standard deviation of wind chill

Solution:

# 1. Calculate wind chill (vectorized!) = temps= wind_speed= 13.12 + 0.6215 * T - 11.37 * V** 0.16 + 0.3965 * T* V** 0.16 # 2. Count below 0 = np.sum (wind_chill < 0 )print (f"Hours with WC < 0°C: { below_zero} " )# 3. Statistics print (f"Mean WC: { wind_chill. mean():.1f} °C" )print (f"Std WC: { wind_chill. std():.1f} °C" )

Hours with WC < 0°C: 24

Mean WC: -6.9°C

Std WC: 3.8°C

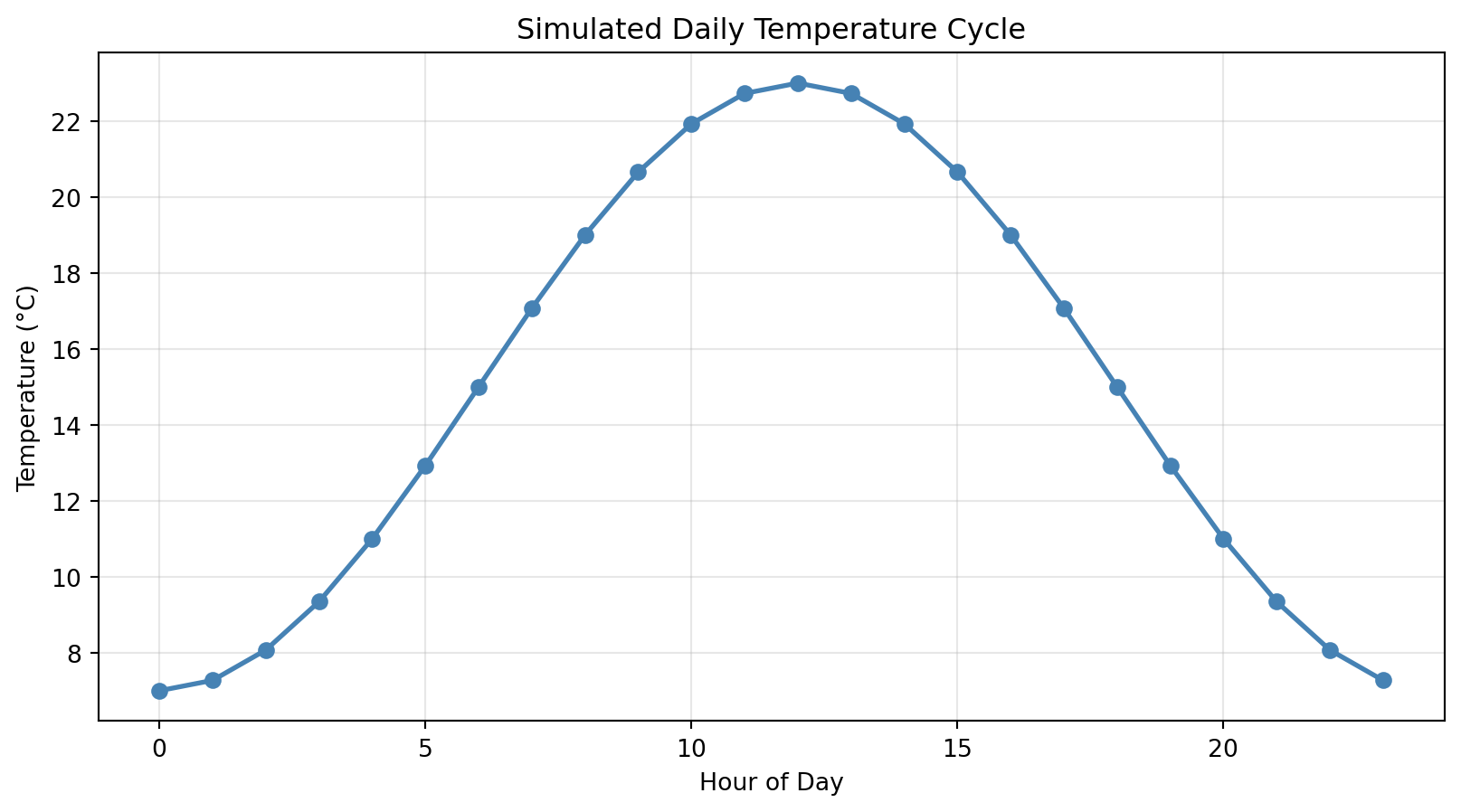

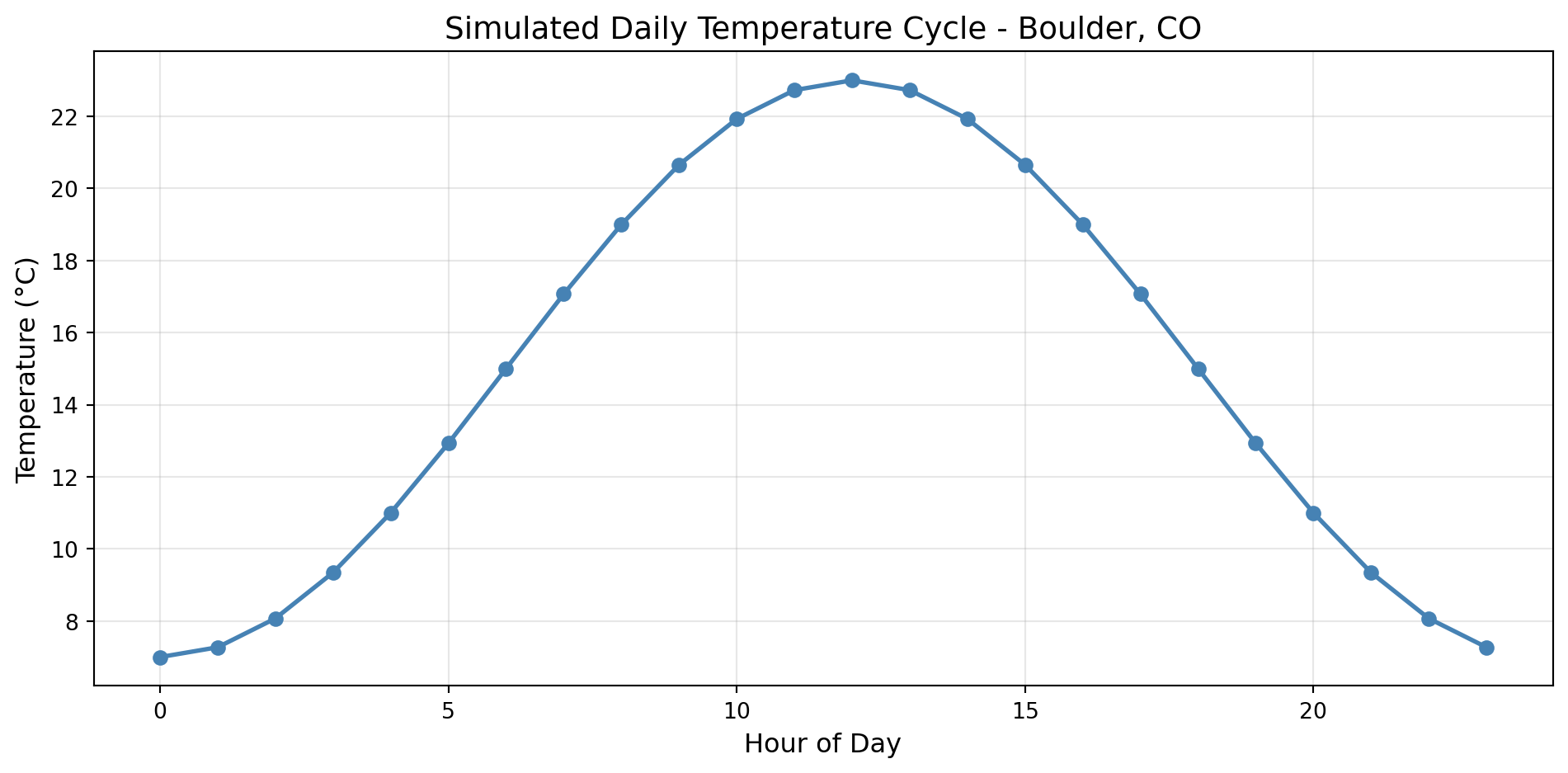

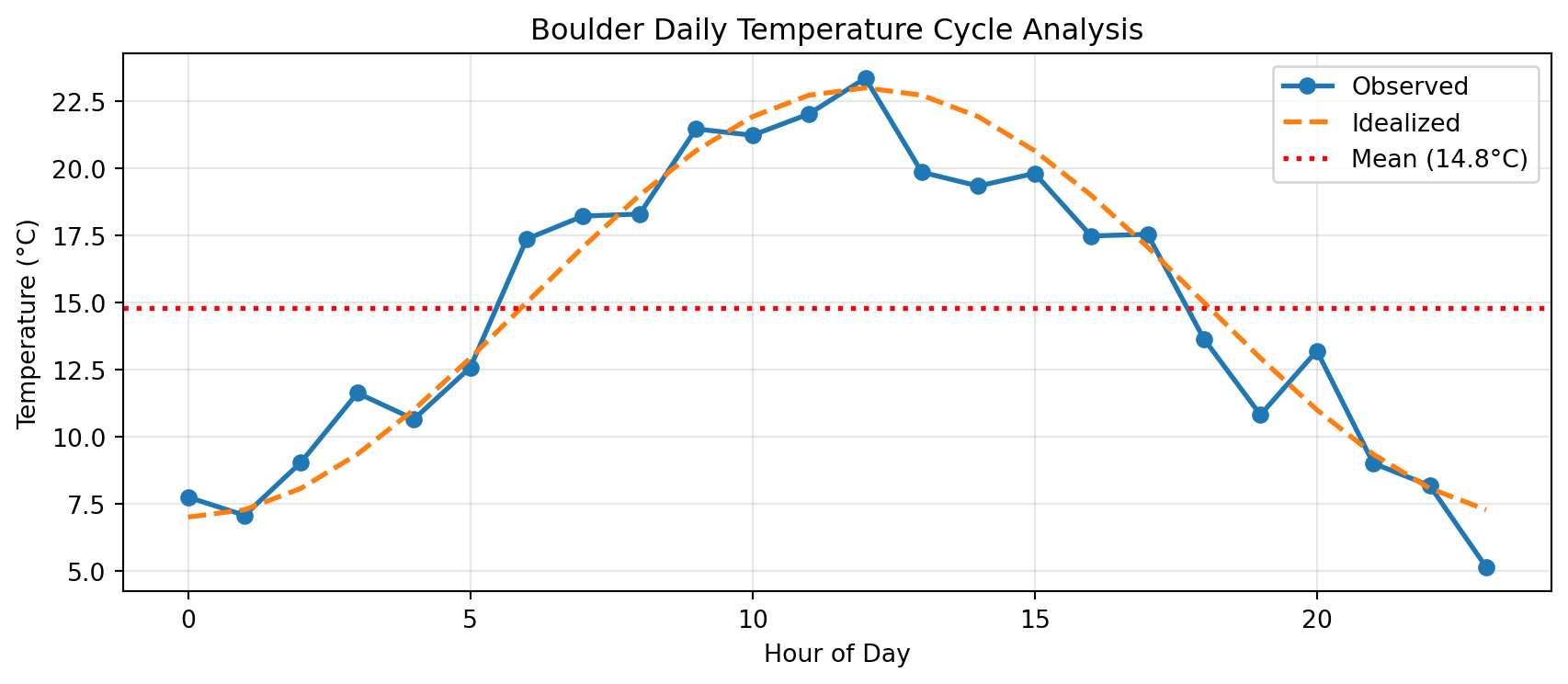

Why Visualize?

Anscombe’s Quartet: Four datasets with identical statistics but very different patterns

# All four datasets have: = 9.0 = 7.5 = 0.816 Without plotting, they look the same!

With plotting:

Dataset 1: Linear relationship

Dataset 2: Quadratic curve

Dataset 3: Linear with outlier

Dataset 4: Vertical line with outlier

Always visualize your data!

Lesson: Statistics alone can mislead. Plots reveal the truth.

Common Error: Forgetting Import

Predict the output:

= np.arange(0 , 24 )= 15 + 8 * np.sin(hours * np.pi / 12 )

NameError: name 'plt' is not definedThe Fix:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # Standard convention import numpy as np= np.arange(0 , 24 )= 15 + 8 * np.sin(hours * np.pi / 12 )

Takeaway: Always import matplotlib.pyplot as plt at the top of your file

Common Error: Mismatched Array Lengths

Predict the output:

= np.arange(0 , 24 ) # 24 elements = np.array([15 , 18 , 22 ]) # 3 elements

ValueError: x and y must have same first dimension, but have shapes (24,) and (3,)Why? plt.plot(x, y) expects x and y to have the same length!

Debugging strategy:

print (f"hours.shape: { hours. shape} " )print (f"temps.shape: { temps. shape} " )# They must match! The fix: Make sure your x and y arrays have the same number of elements

Check Your Understanding 🤔

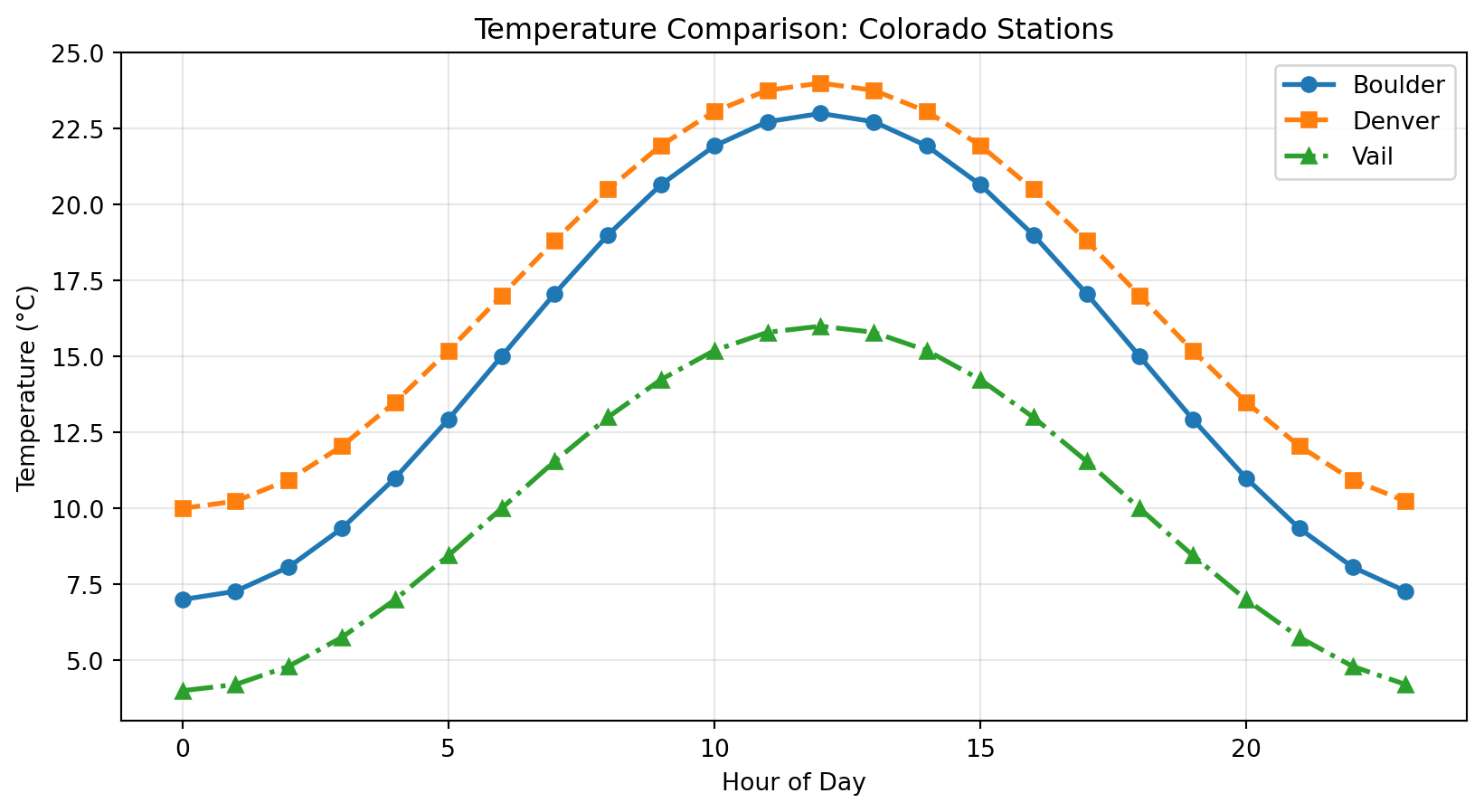

Which plot type would you use for:

Comparing average precipitation across 12 months?

Exploring relationship between humidity and temperature?

Showing temperature change over 24 hours?

Answers:

Bar plot — comparing categories (months)Scatter plot — relationship between two continuous variablesLine plot — showing change over time (continuous)

Key: Think about what question you’re answering!

Try It Yourself 💻

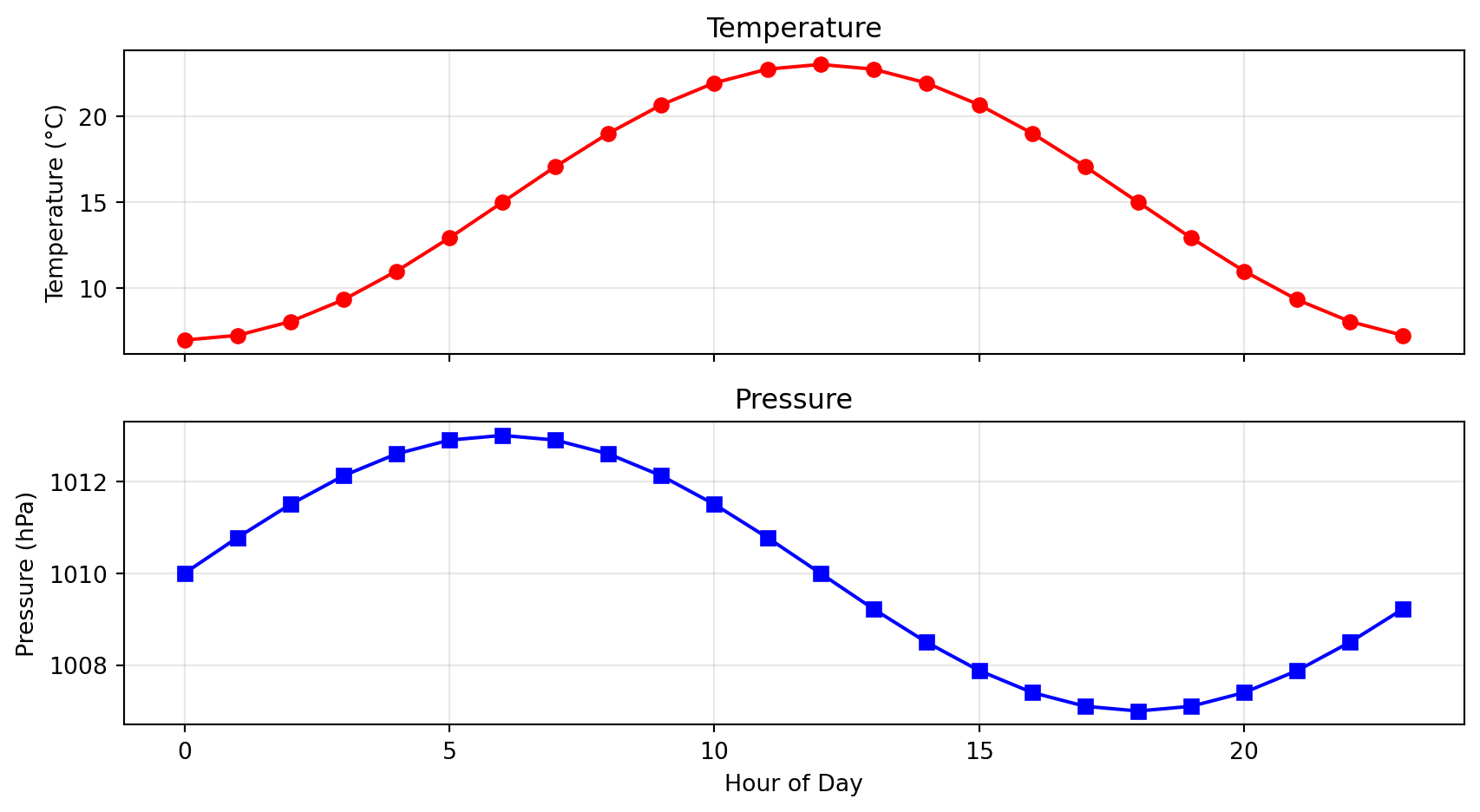

Challenge: Create a 2×2 subplot showing:

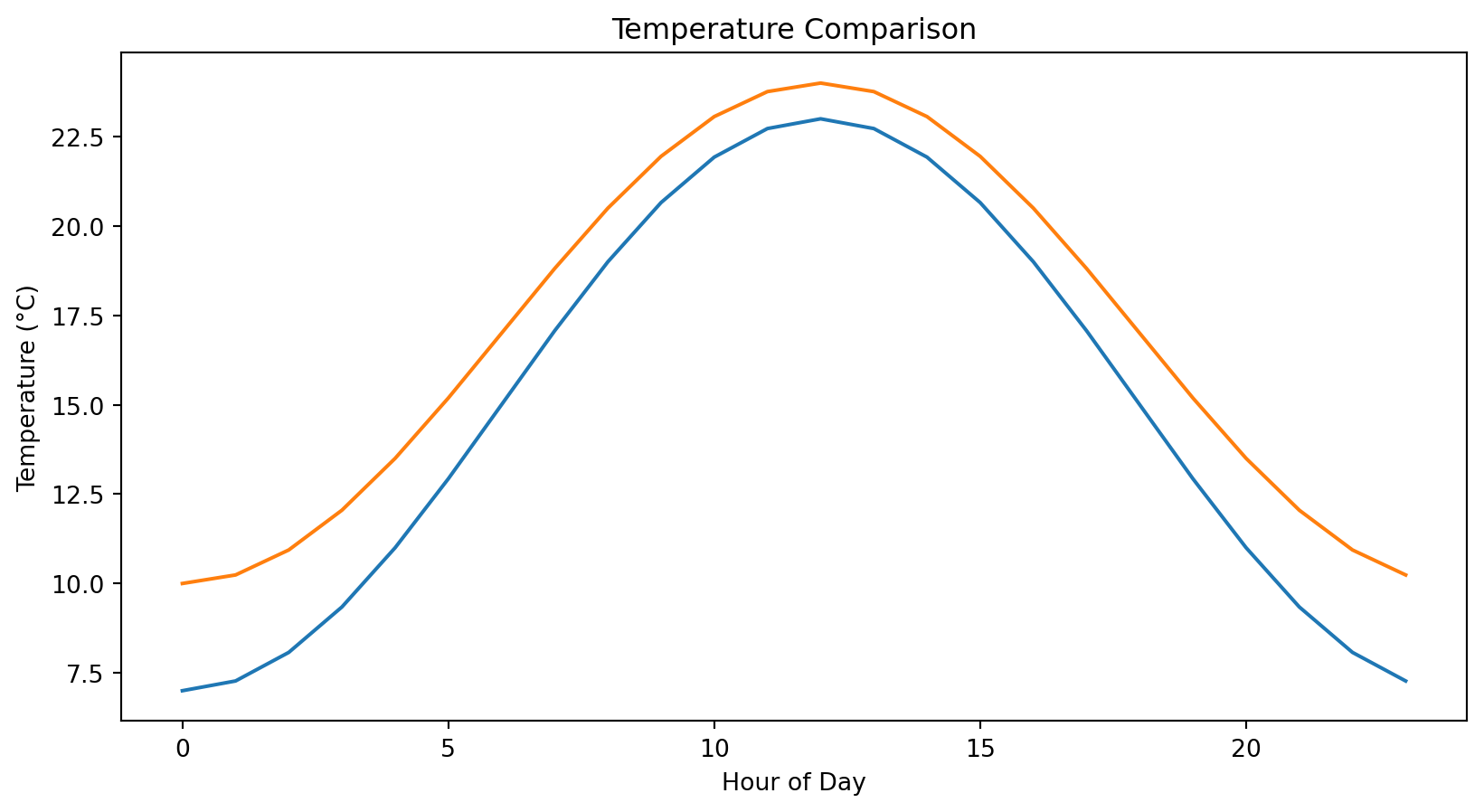

Top-left: Line plot of temperature over 24 hours

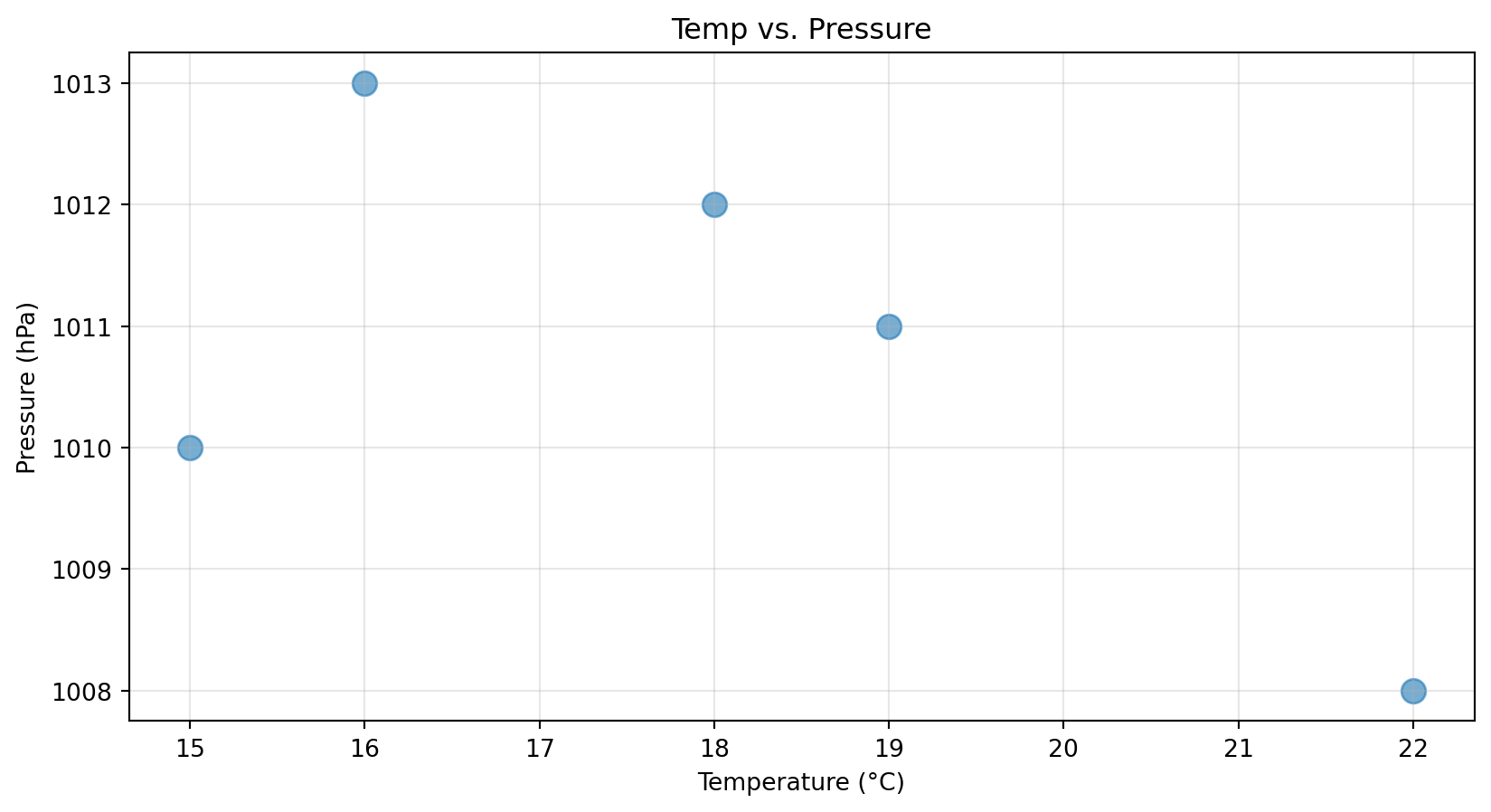

Top-right: Scatter of temp vs pressure

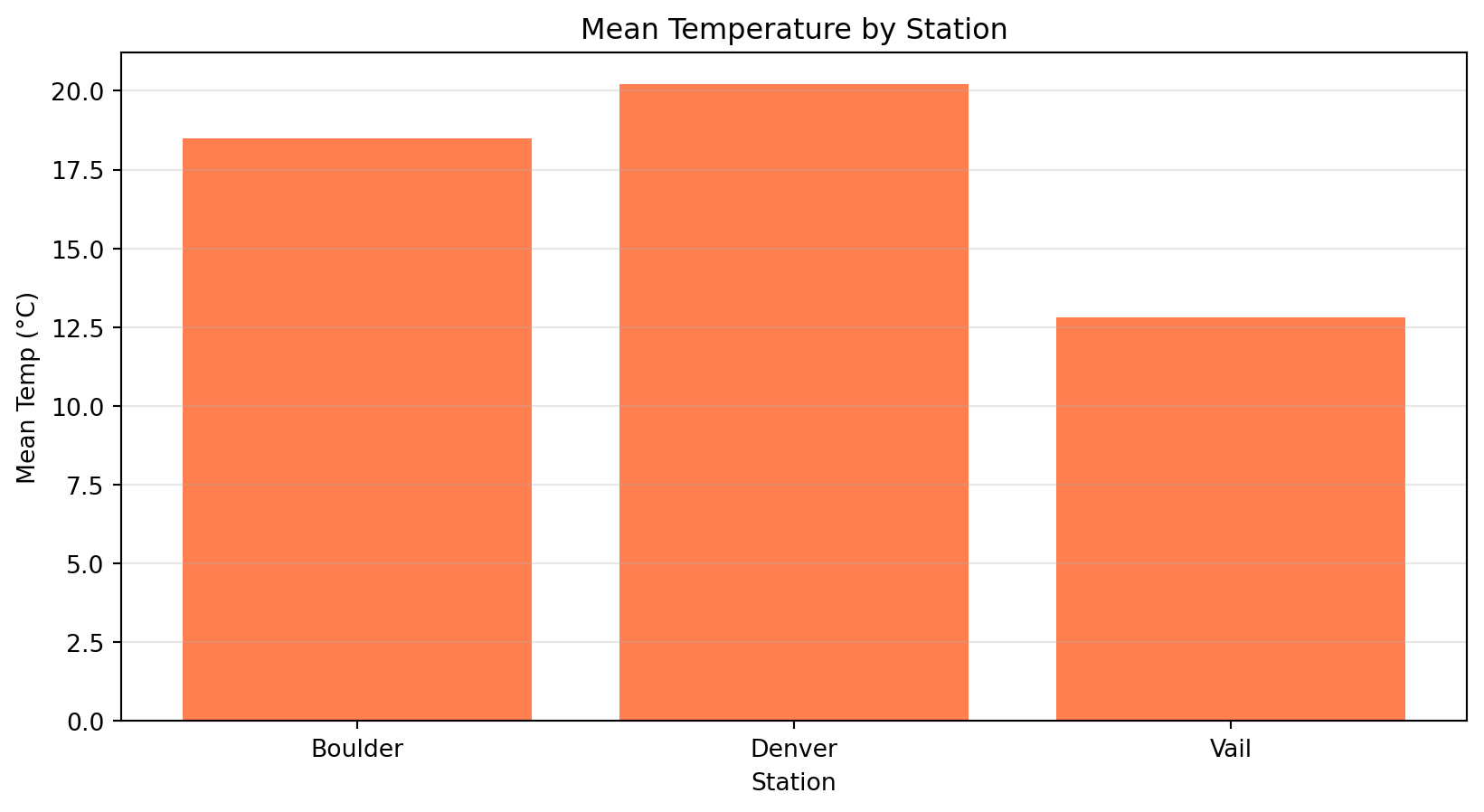

Bottom-left: Bar plot of mean temps for 3 stations

Bottom-right: Histogram of all temperature values

Hint:

= plt.subplots(2 , 2 , figsize= (10 , 8 ))